Aside from the new year itself, the most significant holiday in January in the U.S. is Martin Luther King Jr. Day. This day recognizes the life and work of a man who was a Black civil rights activist and American Baptist preacher from Georgia. Martin Luther King, Jr. was a major figure in the 1950s-1960s desegregation movement in the USA. To understand his work, it’s important to understand the history of his home state, Georgia.

Quick History of Georgia

Georgia: Built from Native Lands

Georgia is a southern U.S. state. (See map above.) Georgia was founded as a slavery/plantation colony in 1733, after European-American colonists arrived but before the USA was an independent country. Georgia changed status from a colony to a state in 1788, after the Revolutionary War (when the USA gained independence from the UK). To create the American territory of Georgia, the colonists increasingly took land away from local Native tribes. (See some of the disputed territory below.)

Broken Promises

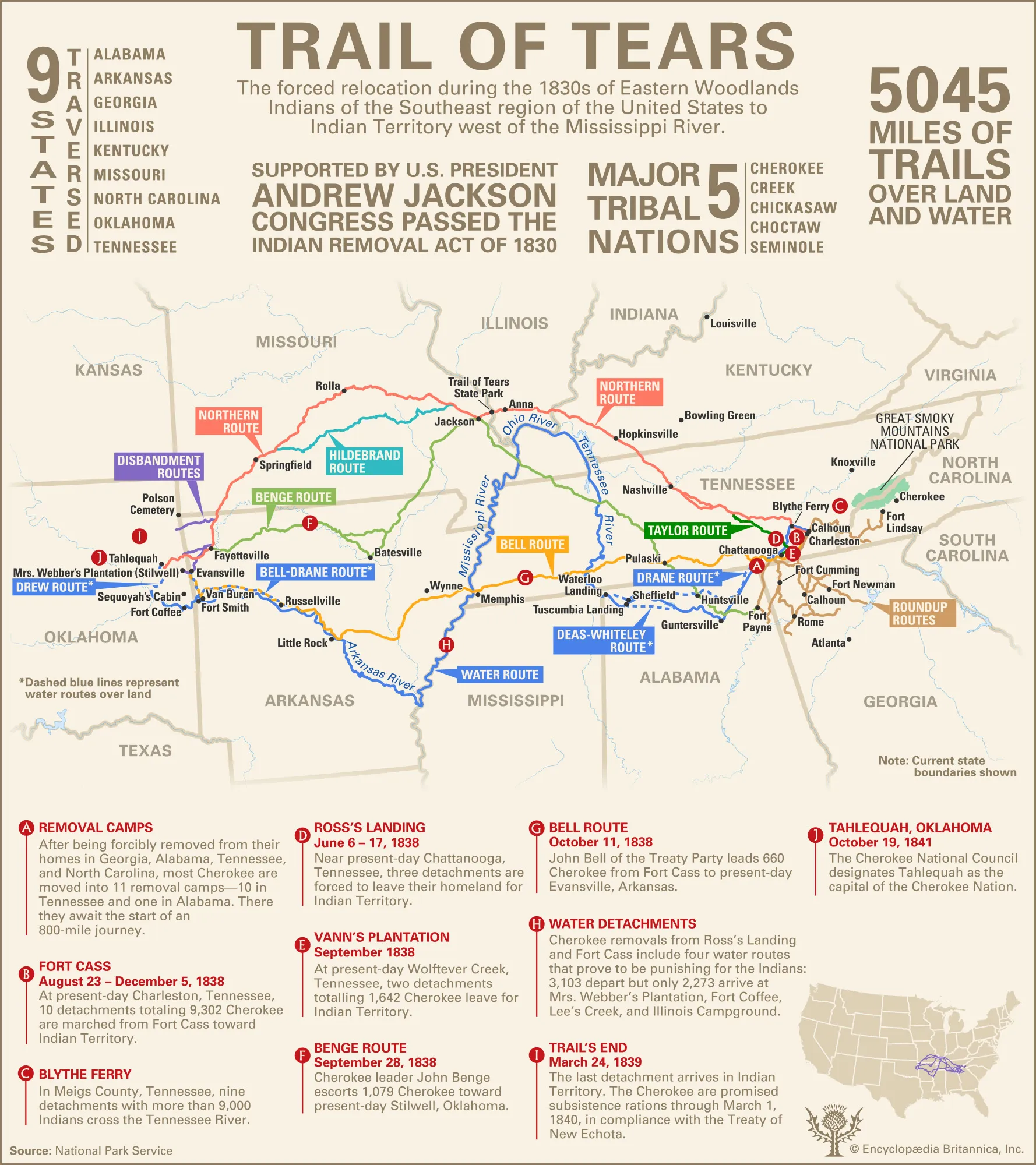

In fact, Georgia had many land disputes with the U.S. government from the beginning of its statehood. It sat on land that was previously inhabited by Native tribes, and its official border was next to land that the U.S. government had promised to leave alone for American Indian tribes, including the Cherokee Nation, the Choctaw, the Seminole, the Creek Nation, and the Chickasaw (then known as the “5 Civilized Tribes”). The tribes had gained the title of “civilized” by adopting some practices of the European settlers, including European-style dress and writing systems but also intensive farming and African slavery. However, Georgia’s colonists wanted this land for their own farms, and they grew more aggressive when gold was found on the land in 1828. This dispute eventually led to the 1830 Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears, in which the U.S. government changed its previous land treaties with the five tribes, ignored an 1831 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in favor of the Cherokee tribe’s rights, and allowed the state of Georgia to force the Cherokee and the other tribes out of their ancestral lands.

Slavery versus Abolition

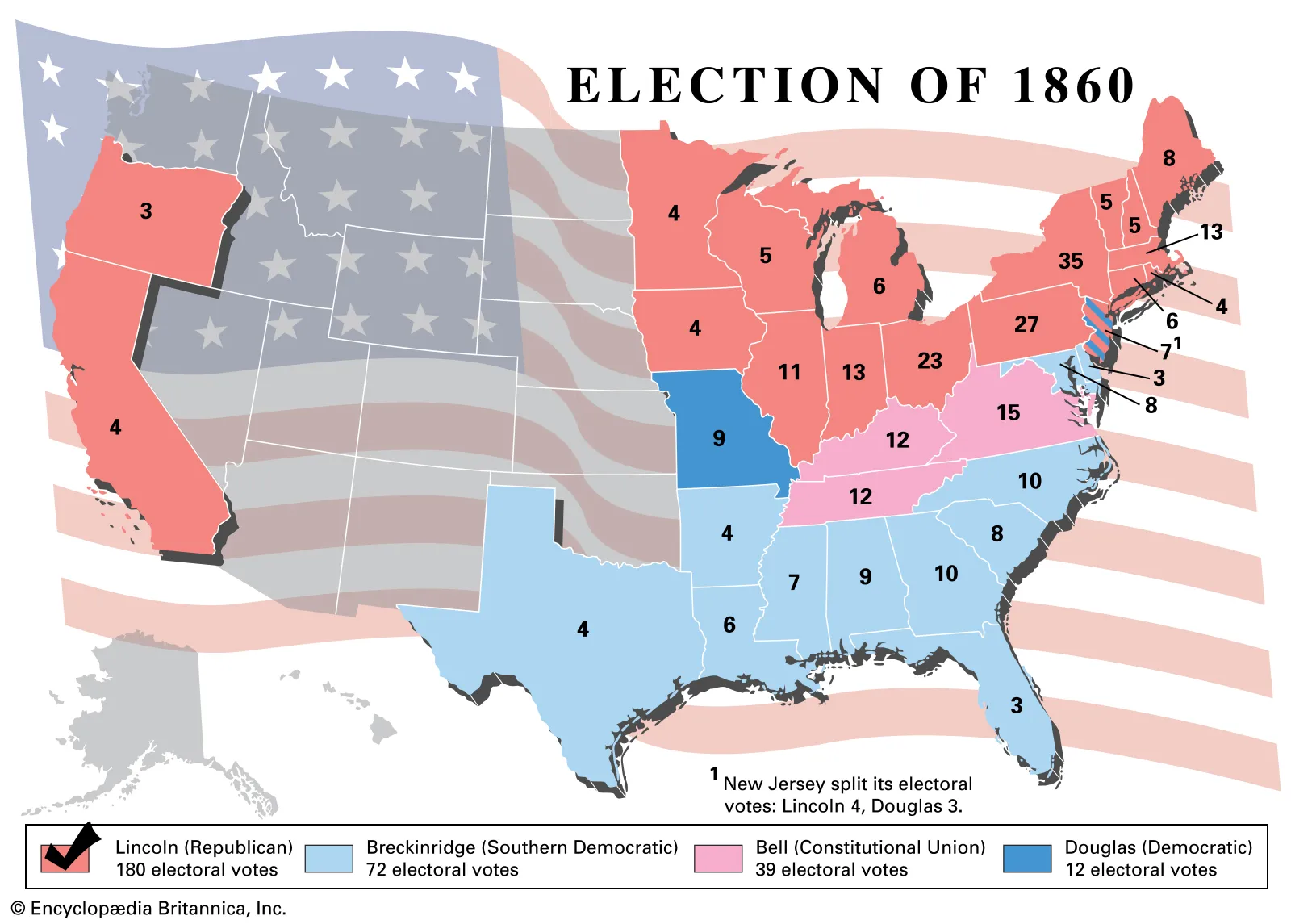

At the time of the United States’ independence, approximately half of U.S. states were slave states and the other half were “free” states. (The slave states were mostly in the southern half of the country where large-scale agriculture was easier.) This arrangement was formally recorded as part of the 1820 Missouri Compromise. However, northern states were increasingly uncomfortable with allowing the brutality of chattel slavery within the country’s borders, and there were people demanding the abolition (end) of slavery in the United States. (It had already been banned in Mexico and in the UK, which still controlled Canada at the time.) Finally, an abolitionist president named Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860.

Secession

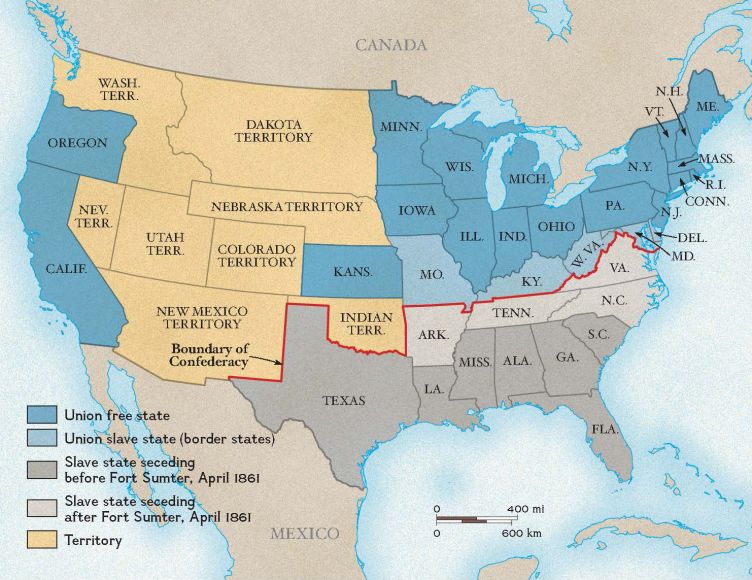

As a result, near the turn of the year from 1860 to 1861, most of the southern slave-owning states decided to leave the U.S. and form a new country with a government that would allow slavery to continue. (To this day, anyone can read the original articles of secession.) The departing states called themselves the Confederacy. (See map below.) They even elected a president, named Jefferson Davis.

Liberation…?

To the confederacy’s dismay, Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware voted not to join them. (Nevertheless, they did have Confederate sympathizers in the state government – see Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware.) In addition, West Virginia is now a state because they separated from Confederate Virginia in 1861. However, members of several American Indian tribes, many of whom were still angry about the U.S. government’s “Trail of Tears” betrayal and/or economically dependent on slavery, did join the Confederacy. Georgia joined the Confederacy in January 1861 and fought to remain a slave state until the end of the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865). In 1863, the 16th U.S. president, Abraham Lincoln, issued the Emancipation Proclamation to free all slaves in the southern, rebelling Confederacy. However, the proclamation was not fully enforced until the end of the war. (See Juneteenth.)

After more than 4 years of war, the Civil War ended in 1865-66. On April 2, 1865, Union (U.S.) forces took over the Confederate capitol of Richmond, Virginia. The Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, ran away with his men. As military commander-in-chief, Davis declared that the Confederacy would continue fighting. However, on April 9th, Confederate military General Robert E. Lee signed the articles of surrender for his troops in Virginia, starting a chain of Confederate military surrenders. Most of Georgia’s troops surrendered at various times throughout April and May of 1865. After President Lincoln was assassinated on April 14th, efforts to capture Davis redoubled, and Davis and his men were captured on May 9th. Atlanta, Georgia’s capitol, surrendered on September 2nd, 1865. Shenandoah, the last Confederate naval ship, surrendered to the UK in November, 1865, and the state of Texas finally surrendered in April 1866.

Resentment and Ongoing Discrimination

The Confederates who had lost the war were very angry and kept trying to hold onto power. On Christmas Eve of 1865, six former Confederate officers in the state of Tennessee decided to form a secret organization called the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which promoted white supremacy and ongoing resistance to reunification across the South. For their disguises, KKK leaders appropriated a Spanish Catholic costume – an odd choice for an organization that was strongly anti-Catholic. Although the original KKK devolved into other white supremacy organizations, it was recreated in Stone Mountain, Georgia in 1915 as the result of the racist movie Birth of a Nation, which promoted the Lost Cause myths and encouraged dehumanizing violence against Black people. The Klan became less active from the late 1920s (during the Great Depression/Dust Bowl resettlement and World War II) and was officially disbanded in 1944 to avoid tax liabilities, but was “reconsecrated” at Stone Mountain in 1946. When it returned, it was quickly decentralized into many smaller, separate groups, and its overall goal focused on attacking fewer demographics (more specifically, Black people and their allies), leading some scholars to distinguish between the “second Klan” and “later Klans”. It was particularly active during the Civil Rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, rising up in opposition to civil rights efforts. Throughout all three Klan periods, state and local governments and the state and local police forces, were often filled with white supremacists who sought to hold onto power. As a result, those police and governments were ineffective against, or sometimes actively enabled, violent white supremacist crimes such as beatings, rape, lynchings, murders, house burnings, and bombings. Although its membership and political power have severely declined in recent years, the KKK still exists to this day, as do similar groups with different names but the same goals.

The Ku Klux Klan (/ˌkuː klʌks ˈklæn, ˌkjuː-/),[c] commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans,[43] and Catholics, as well as immigrants, leftists, homosexuals,[44][45] Muslims,[46] atheists,[27][28][29][30] and abortion providers.[47][48][49]

Wikipedia, “Ku Klux Klan”, 1/5/2023

Georgia, like the other Confederate states, was forced to end its practice of African-American slavery after the war. As a result, Georgia’s local government (which was still full of former Confederates, many of whom became Klan members, and their descendants) was still hostile to Black people and their allies well into the 20th century. (Some people would argue that it still is.) Georgia, like other states in the former Confederacy, passed “Jim Crow” laws that segregated “colored” and “white” people into different neighborhoods (for example, “redlining“), different schools, different train cars, and even sections of a bus (“white” people in the front half, “colored” people in the back half). “Colored” included anyone who was identified as even a small part Black, any Native or Hispanic people, and anyone who was South/East Asian, Middle Eastern, or Jewish, unless they could “pass as” (successfully pretend to be) white. Because of the pressures, many people tried to pass as white, or at least avoid the “colored” label, even though they were abandoning their heritage and reinforcing racism and white supremacy by doing so. Although defenders of segregation liked to claim that they were pursuing a policy of “separate but equal,” resources for “colored” people were not the same quality as the resources for “white” people. In fact, the resources for white people were clearly superior to the resources for people of color. In addition, the laws were clearly biased because only “colored” people were prosecuted for crossing into “white” spaces; “white” people were not prosecuted for being in “colored” spaces. For these reasons and many others, most Black Americans were not happy about segregationist policies.

However, in the 1900s, some Black Americans actually advocated for a separate nation to be founded for Black people in America. Some people, such as Malcolm X (a famous Black civil rights activist from Nebraska) and members of the 1967 Conference on Black Power in New Jersey, advocated for the separatist policy so that Black people could control their own lives. Others, such as the founders of the Nation of Islam, believed in black supremacy (an opposing and equally discriminatory ideology to white supremacy, but with less political power). Malcolm X’s public participation in this ideology served as a contrast, and briefly as indirect support, to the political movements led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Childhood

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (sometimes known as MLK or Dr. King) is named after a famous Christian minister named Martin Luther – the first Protestant minister. However, MLK Jr. was born Michael King Jr. in 1929, named after his father. His father, who was named Michael King Sr. at that time, was also a Baptist (type of Christian) minister. When King Jr. was 5 years old, his father traveled to Berlin, Germany for a religious conference in 1934 and saw the Nazi politics increasing in popularity. King Sr. condemned the racial hostility that filled Nazi ideas. After the trip, he changed his name and his son’s name to Martin Luther King.

Although King Sr. was raised under discriminatory segregationist policies in Georgia, he taught his son to never see the discrimination as acceptable. King Jr. grew up in segregationist Georgia as well. Being surrounded by discriminatory policies tempted him to hate all white people, but his father encouraged him to love his neighbors in the Christian way. King Jr. finished high school and went off to college at the age of 15, and his summer job was in the state of Connecticut – in the northeastern USA, which did not have segregation policies. There, he was able to meet and spend time with white people who did not discriminate against him. He realized that the problem was in his region’s policies.

Adulthood and Advocacy

After King Jr. finished his studies at Morehouse College, he decided to go to seminary and become a Baptist minister like his father. He also completed a doctorate in theological studies. He met and married Ms. Coretta Scott, and they had 4 children together during his early years as a minister.

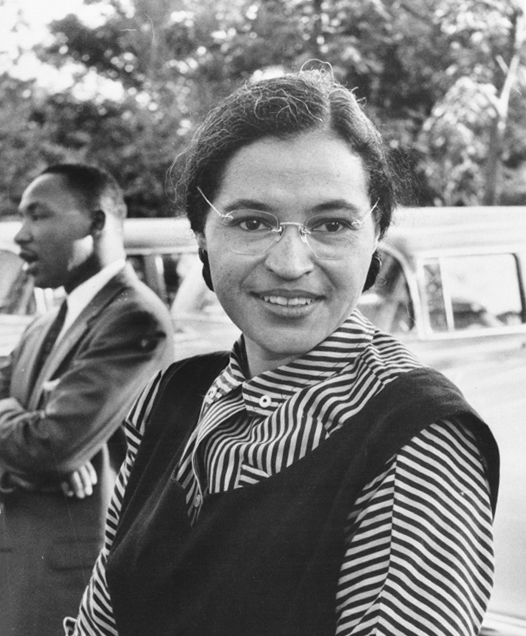

In 1955, Dr. King started getting involved in civil rights protests. The first major civil rights issue to feature his involvement was the arrest of Rosa Parks, a 42-year-old Black woman who refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955. At the time, the city of Montgomery had a law to separate white passengers from other passengers on public buses. However, the sign that was used to separate the two sections was moveable, and (white) bus drivers would regularly move the sign backwards and order Black passengers to move (or stand) so that all white passengers could sit down. One day, a particularly rude bus driver saw that one white passenger didn’t have a seat, so he ordered 4 Black passengers to move, clearing an entire row to create more “white” space. The other three passengers moved, but Mrs. Parks was angry and tired of the discrimination, and she was still grieving the death of Emmett Till, so she refused to move. The driver called the police, and she was arrested. After her arrest, Dr. King was chosen by other civil rights leaders to lead a 385-day bus boycott – in other words, for 385 days, people of color avoided using any public buses in Montgomery. The bus companies lost a lot of money without those passengers, so they started to reconsider their support of the city policy. As a result of his public involvement in the protest, Dr. King was arrested by local police for driving 30 mph in a 25 mph zone, and his house was bombed. The next year, in 1956, the Supreme Court case Browder vs. Gayle finally resulted in the desegregation of the Montgomery public buses. However, Dr. King had discovered the path of civil protest, which would shape the rest of his life.

In 1957, Dr. King and other civil rights leaders started the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was an organization of churches working together to support civil rights efforts. He became the organization’s first president.

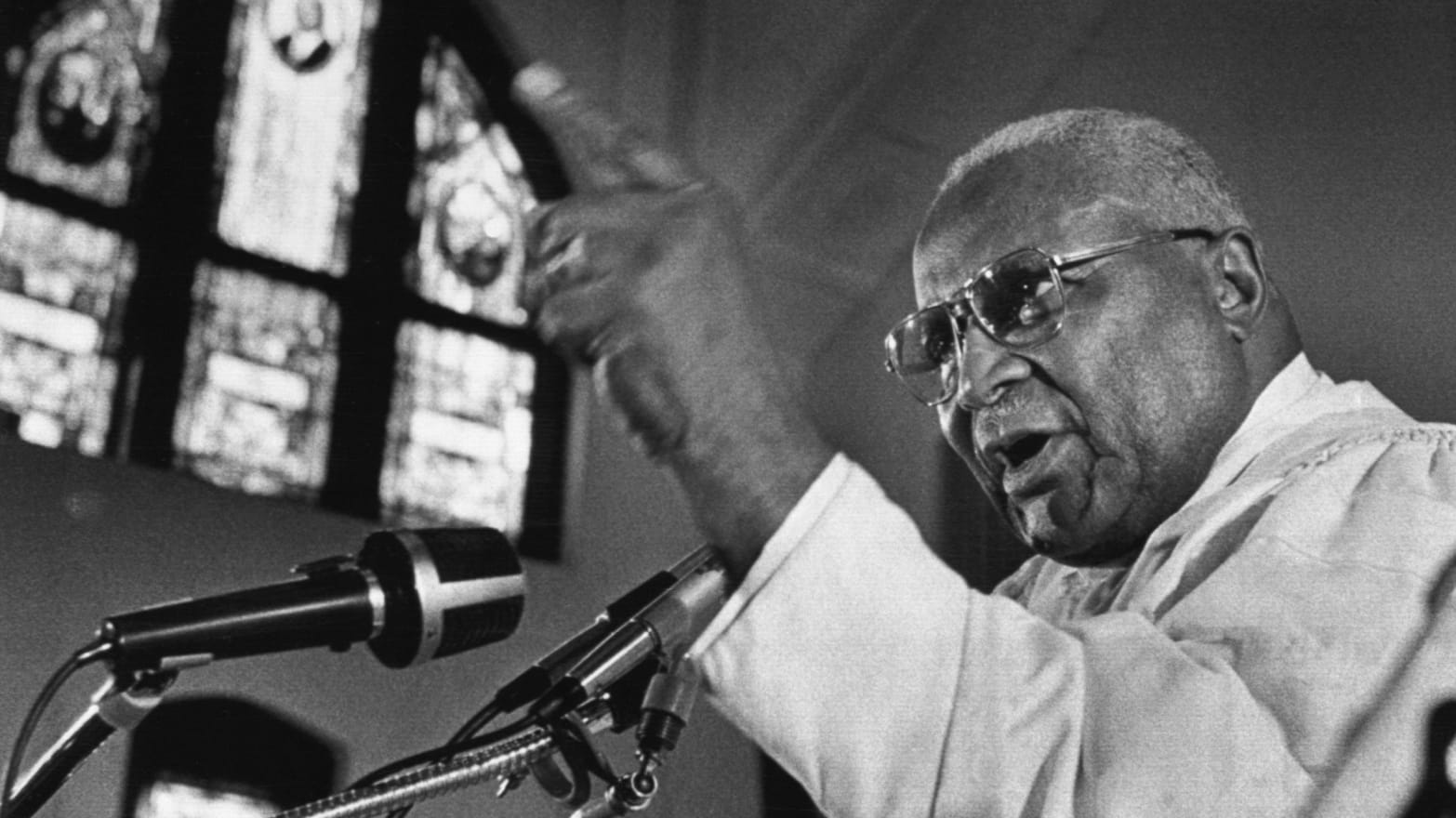

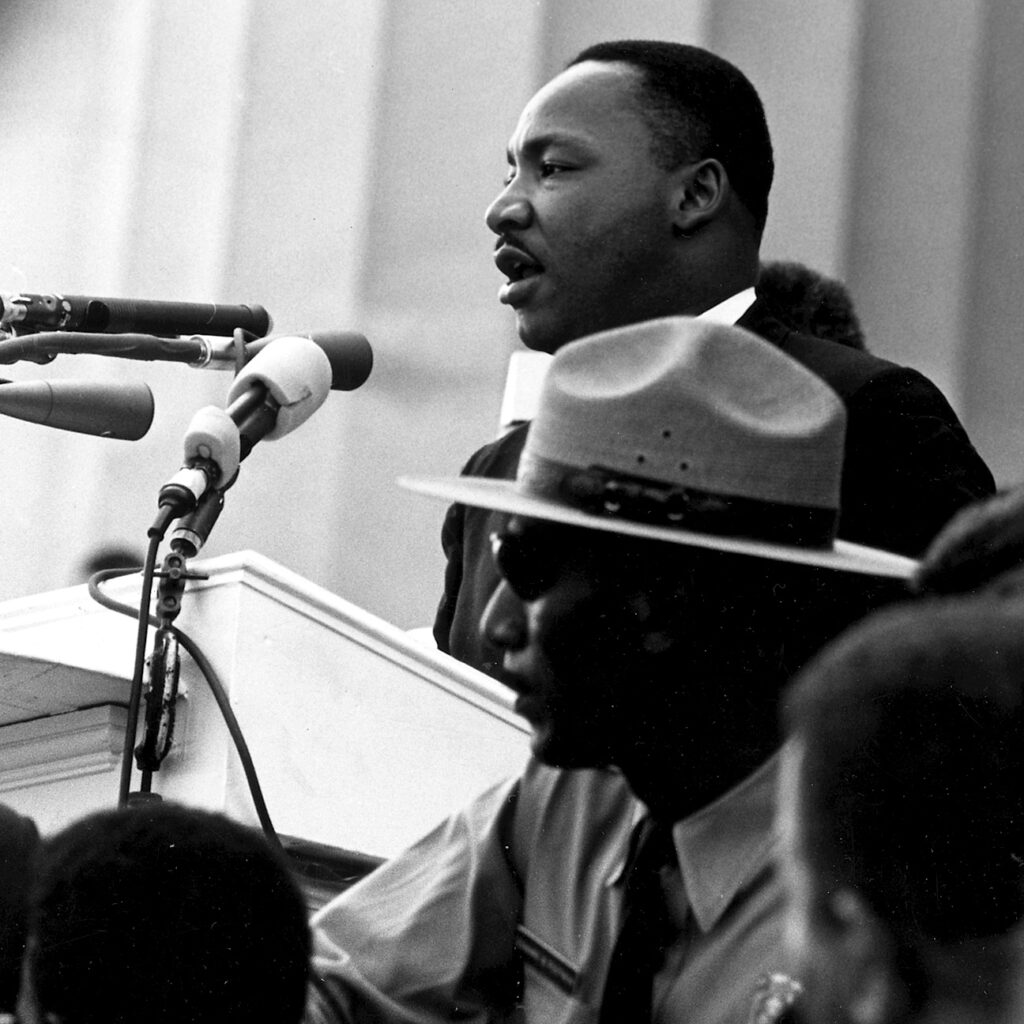

Throughout his life, Dr. King admired and tried to live by Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violent protest (satyagraha, or peaceful non-compliance), and he even visited Gandhi’s birthplace in India in 1959. King Jr.’s idealization of non-violent protest strategies was supported by his friend, Bayard Rustin, who encouraged him to take non-violence a step further by not owning guns. Rustin was also instrumental in organizing many of the protest marches and speeches that Dr. King participated in as a public figure, including the famous 1963 March on Washington (see image, 4 paragraphs below). Rustin remained a background figure because of his sexuality and his previous membership in the American Communist Party, but he and Dr. King remained friends during Dr. King’s lifetime.

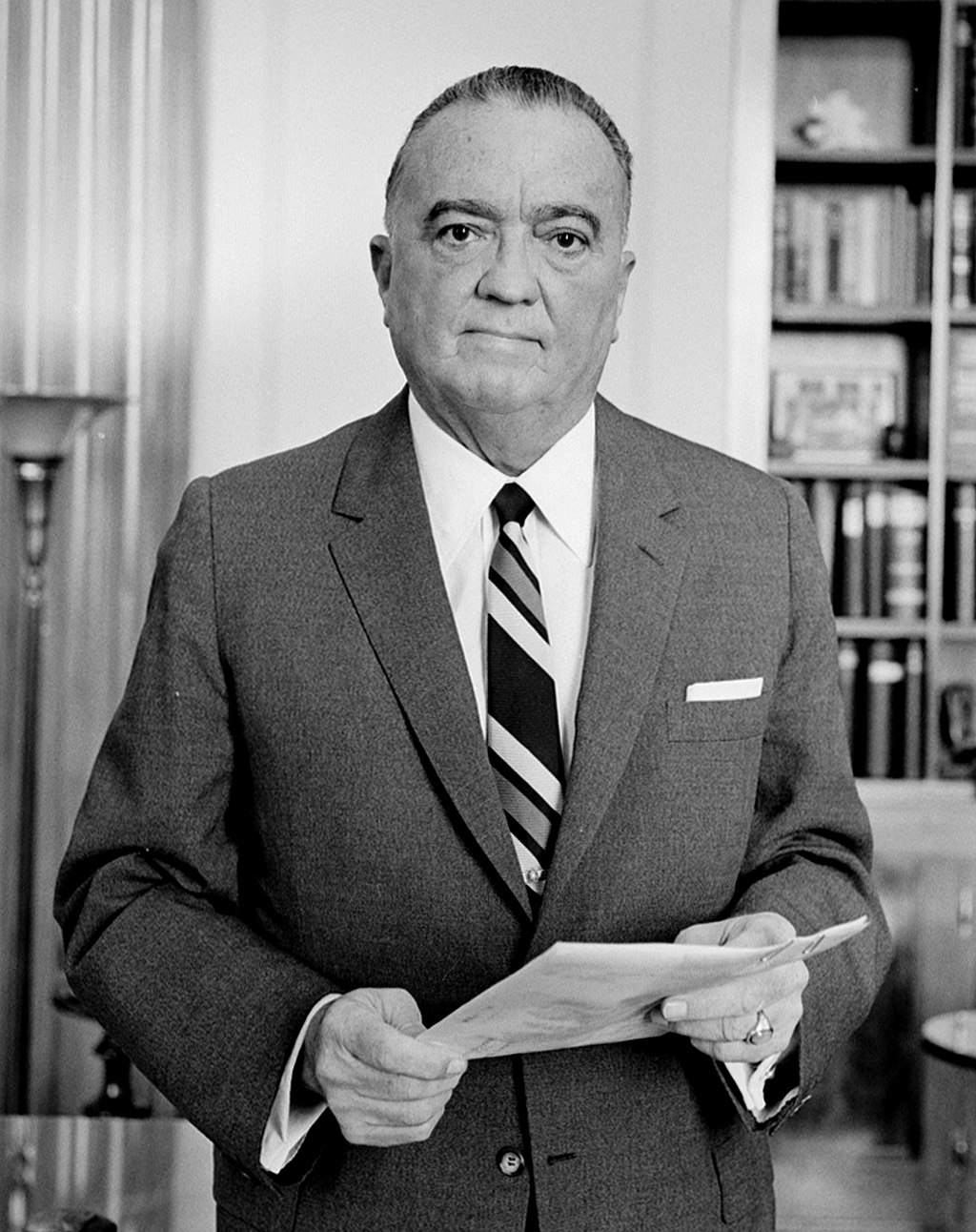

In the early 20th century, “regime changes” were rampant, and many Americans watched the violent political upheavals in Russia and China and became afraid of Communism. (Some still are.) Efforts to prevent Communism in the United States were known collectively as the “Red Scare“, and anyone who was associated with Communism was seen as a threat to national security. Critics of Dr. King tried to use his friendship with Rustin as evidence that Dr. King was secretly a Communist (as well as Dr. King’s professional relationships with two other alleged Communists, a lawyer named Levison and an SCLC colleague named O’Dell). But even under the rigorous methods of the FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, which included wiretapping, the FBI never found any evidence to prove their fears. However, when Hoover’s 1964 public accusation that Dr. King lied about his knowledge of Levinson and O’Dell’s Communist ties caused the public to defend Dr. King rather than to trust in the FBI director, King’s social power became clear.

In October of 1960, Dr. King was involved in a famous restaurant sit-in with student protestors in an Atlanta, GA department store. Copying the strategies of the Greensboro Four, university students went to a lunch counter and ordered food, and when the employees refused to serve them food, they sat in their seats and refused to leave. Lunch counter protests of this kind, called “sit-ins,” continued across the South, including in Jackson, Mississippi, Nashville, Tennessee, and Arlington, Virginia. Sometimes, supportive white students would sit together with the Black students in solidarity. Other times, Black students would protest by themselves. As a result of the student protests, the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee was founded, of which the late Rep. John Lewis was an influential founder. Similar non-violent protests occurred on buses that year and for the next few years; the bus protests were called “freedom rides” and were supported by the NAACP.

In 1963, Dr. King attended protests in Birmingham, Alabama. At that time, Birmingham had a city Commissioner of Public Safety who “had administrative authority over the police and fire departments, schools, public health service, and libraries” (Wikipedia, “Bull Connor“). Bull Connor was hostile to the protestors and ordered his officers to hit the protestors with sticks and batons. When the protestors refused to leave, he ordered firefighters and police officers to use fire hoses and attack dogs on the protestors, including on children. Many protestors were badly hurt by the police, dogs, and fire hoses, and the images of protestors’ injuries became a source of motivation for people across the country to fight discrimination. Dr. King was arrested and put in jail in Birmingham, but he refused to let anyone pay his bail and used the time to write a letter to white ministers across the country. This letter, known as the Letter from Birmingham Jail, is now one of his most famous essays.

Later in 1963, Dr. King attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a combined event for racial justice and workers’ rights that brought more than 250,000 people to Washington, D.C. to protest against unfair treatment. (See the official schedule, watch videos, read about memories.) There, he delivered his most famous speech, “I Have a Dream“:

Dr. King’s call for unity was in strong contrast with The Ballot or the Bullet speech by Malcolm X (audio), which was given only a few months later. (Malcolm X regularly criticized the pacifist efforts of Dr. King, believing them to be ineffective, but he later revised his views on race after traveling on a pilgrimage to Mecca.)

Many changes happened quickly after the March on Washington. In November of 1963, President Kennedy, who supported the civil rights movement, the decolonization of Africa, and efforts to pass new civil rights laws, was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. In In March of 1964, Dr. King met with Malcolm X after the latter left the Nation of Islam and gained the freedom to meet with other civil rights group leaders. In July of 1964, the Civil Rights Act finally passed and was signed into law. In December of 1964, Dr. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his non-violent efforts to promote civil rights. In February of 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated by radicalized members of the Nation of Islam; after his death, Dr. King wrote to his widow. On Sunday, March 7th, 1965, about 600 civil rights protestors attempted to walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma, Alabama to attend a protest march against segregation in the state capitol, Montgomery. Dr. King was not present because he was delivering a sermon at his church, but he later regretted his absence that day because many protesters were beaten and tear-gassed by local government leaders in an event that became known as Bloody Sunday. Two days later, on March 9th, Dr. King led a second march to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma and led the protestors in a peaceful prayer, then asked them to leave peacefully to follow the recent order given by the state court. As a result of the violence seen on Bloody Sunday, Congress finally passed the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Malcolm X’s death also spurred the creation of the Black Panther Party, who split from Dr. King’s ranks to endorse militant protection of the Black community across the U.S. through armed confrontation of police brutality. However, they also engaged in community support programs such as free breakfast for children and were (eventually) more welcoming to female leaders than the traditional gender roles maintained in the original civil rights movement. They became famous for their iconic outfits: black leather jackets and berets.

By 1966, in response to the concerns raised by the Black Panther Party and other concerns raised by working-class white allies, Dr. King’s efforts had largely shifted focus from “black liberation” to “liberation of the poor.” He participated in a march against discriminatory housing loan practices in Chicago, known as the Chicago Freedom Movement, and in 1967, he spoke out against America’s participation in the Vietnam war. Finally, in April of 1968, Dr. King went to Memphis, Tennessee to support a workers’ union strike as part of the Poor People’s Campaign. He gave a speech in a Memphis church on April 3rd, after surviving a bomb threat on the plane to Tennessee. He referenced the ongoing threats to his life in his speech, I’ve Been to the Mountaintop, and gave a prophetic ending to the speech by saying that he might not see the end of the fight, but that the effort would continue nonetheless. The next day, on April 4th, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated on his hotel balcony.

Much of his later legacy is “conveniently” forgotten by people who want to believe that progress has already been achieved and that Dr. King’s legacy is complete. However, the truth is more complicated.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Legacy

After MLK Jr.’s untimely death, many cities erupted in violent protest. One week later, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was passed after being rushed through Congress in order to show government action in the wake of a major tragedy; it is now known as the Fair Housing Act.

Dr. King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, continued his advocacy for civil rights. She founded The King Center and continued to fight for recognition of his work. There is also a King Institute at Stanford University and another King Institute in Norway.

The Black Consciousness Movement (anti-apartheid) in South Africa drew elements of strategy from Dr. King’s non-violent resistance methods.

John Hume, a national Irish politician during the Troubles, was inspired by Dr. King (from 18:20) in his decision to fight for civil rights and fair housing in Northern Ireland. When Hume later won a Nobel Peace Prize for his work on the Good Friday Agreement (also known as the Belfast Agreement or the Northern Ireland Peace Agreement), he called Dr. King one of his heroes.

An elementary schoolteacher named Jane Elliot started a “Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes” experiment with her class on the day after Dr. King’s death, an anti-discrimination lesson that she continues to this day.

There is now a federal holiday called Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The holiday observance started in St. Louis MO in 1971, passed nationally in 1983, and was first observed as federal holiday in 1986. It is held on the third Monday of January (this year, January 16th). The last 3 states to start recognizing the day as a state holiday were Arizona, Utah, and New Hampshire – in 2000. (It is also observed in Hiroshima, Japan.) However, the holiday is still known by problematic alternative names in some states (see below).

Ongoing Concerns, 55 years after MLK Jr.’s Death:

Usually, stories about Dr. King end on a positive note about his legacy; however, it would be an insult to Dr. King’s legacy to claim that the work is done. For starters, his legacy is not as respected as it should be.

From Wikipedia: “While all states now observe the [MLK] holiday, some did not name the day after King. For example, in New Hampshire, the holiday was known as “Civil Rights Day” until 1999, when the State Legislature voted to change the name of the holiday to Martin Luther King Day.[25]

Several additional states have chosen to combine commemorations of King’s birthday with other observances:

- In Alabama: “Robert E. Lee/Martin Luther King Birthday”.[26]

- In Arizona: “Martin Luther King Jr./Civil Rights Day”.[27]

- In Arkansas: it was known as “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Birthday and Robert E. Lee’s Birthday” from 1985 to 2017. Legislation in March 2017 changed the name of the state holiday to “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Birthday” and moved the commemoration of Lee to October.

- In Idaho: “Martin Luther King Jr.–Idaho Human Rights Day“.[28]

- In Mississippi: “Martin Luther King’s and Robert E. Lee’s Birthdays”.[29]

- In New Hampshire: “Martin Luther King Jr. Civil Rights Day”.[30]

- In Virginia: it was known as Lee–Jackson–King Day, combining King’s birthday with the established Lee–Jackson Day.[31] In 2000, Lee–Jackson Day was moved to the Friday before Martin Luther King Jr. Day, establishing Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a holiday in its own right.[32] Lee-Jackson day was eliminated in 2020.[33]

- In Wyoming: it is known as “Martin Luther King Jr./Wyoming Equality Day”. Liz Byrd, the first black woman in Wyoming legislature, introduced a bill in 1991 for Wyoming to recognize MLK day as a paid state holiday; however, she compromised on the name because her peers would not pass it otherwise.[34]“

In other words, there were 4 states, and there are still 2 (Alabama and Mississippi), that recognize Dr. King on the same day as a former Confederate leader.

In fact, the theme of an un-surrendered Confederacy lingers in many places: As of 2015, five U.S. states still contained elements of the Confederate flag. The battle flag of the Confederacy is still flown by rebellious people who hold white supremacist sentiments, whether disguised as anti-vaccine protests in Canada or made clear by insurrectionists at the U.S. Capitol. The Gadsden “don’t tread on me” flag, originally an American revolutionary flag but also briefly a flag of the Confederate navy, is still used by openly pro-Confederate groups such as the KKK. (It is also regularly used by right-wing libertarians in a historical reference that is not clearly labeled as non-Confederate.) White supremacy was the main cause of domestic terrorism in the U.S. There are still monuments to Jefferson Davis, the president of the short-lived Confederacy. The birthday of Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, is still celebrated at a state level in four states. The Edmund Pettus Bridge is still named after a Confederate leader and member of the KKK. There are still Confederate names on 9 U.S. military bases (though there are ongoing efforts to change the names) and on schools across the country, including schools in states that were never part of the Confederacy. Many of the schools now serve as the local school for communities of Black, Indigenous, and/or Hispanic children, creating a hostile educational environment for them. White residents often fail to see the problem with their school’s name, defending “history” or the “legacy” of the name, or relying entirely on personal sentiments of school pride. Even though it has been denounced as false since 1866, the Confederate Lost Cause narrative lives on, leading to extensive discussions among educators and historians about how to preserve and teach the truth. These discussions are increasingly difficult due to strong political backlash from conservative politicians who label all inconvenient truths as “critical race theory” and defend Confederate monuments.

The biggest political irony is that, due to the Southern strategy of the mid-20th century, Republicans (also known as the GOP) are now the political party that is pandering to racist beliefs (from Wallace to Trump, especially in the South) and protecting the false narrative, despite having begun as the anti-slavery party of Lincoln. (The Southern strategy was very effective in changing the party’s demographics to reflect anti-civil-rights ideals. Even after the white supremacist-led attack on the Capitol, shockingly few Republican politicians are participating in civil rights advocacy or calling themselves Lincoln Republicans, much less condemning covert supremacist ideology in their colleagues or joining the Lincoln Project. It has gotten so severe that even the former chair of the Republican National Committee claimed that Black people “had no reason to” vote for Republicans.) An analysis by the Guardian UK shows that the historical issue is not so much “Republican versus Democrat” as it is “Former Union versus Former Confederacy”. In other words, members of both political parties have historically corrupted themselves in order to appease Southern white supremacists – first the Democrats, and now the Republicans. Nevertheless, it is notable that the Democrats of the 1860s and 1960s were never as nationally unified on discriminatory policies (and race-baiting) as the Republicans of the 2020s are showing themselves to be.

It’s not all bad news! An African-American director named Nate Parker set out to reclaim the title “Birth of a Nation” when he made a 2016 movie about Nat Turner, leader of a slave rebellion. In 2021, a Baptist pastor named Raphael Warnock was elected the first Black U.S. senator from GA, and Black political figures in Georgia such as Stacey Abrams are on the rise. Even though some people still defend white supremacy and the Confederacy itself, everyone can agree that Bull Connor was a terrible person.

But arguably of greater concern for Dr. King would be the anti-racism and anti-poverty policy changes that have yet to occur – or that have been undone. Voter protection laws are being amended or repealed. Although the March on Washington led to an increased and expanded minimum wage that helped Black families, the federal minimum wage is still low and still disproportionately affects Black workers. In August 1963, Dr. King advocated for $2/hour, which is worth $19.39/hour in November 2022 dollars, but the federal minimum wage is currently $7.25/hour. There is still housing discrimination among landlords, real estate assessors, loan providers, and private sellers and buyers. Unscrupulous capitalists have found ways around the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution (ostensibly banning slavery) through exploitation of private prison populations. Rich political advocates are still lobbying for austerity measures to lower their taxes at the expense of public services for low-income people, and people depending on programs to prevent poverty and child hunger still receive far less funding than the cost of living demands. In addition, even when costs are adjusted for purchasing power parity, the U.S. government is still spending a lot of money to support wars and armed conflicts around the world. All of these are issues that would concern or upset Dr. King.

Many people don’t even realize that Dr. King supported these other issues, as they only hear about his desegregation efforts. Segregation is now illegal in the USA, so it’s easy to pretend that his goals were met. However, that would not be an honest representation of history. Thus, it is important to teach a more complete picture of MLK.

Thinking about the issue: “Passing” (pretending to be the dominant ethnicity) is still an issue today in many societies – both because of colorism and because of other ongoing discrimination. (For examples in Japan, see social discrimination against being “ハフ” or actions by people of Korean or Chinese descent in Japan to hide their citizenship status in their social lives.) Having multiple cultural identities is also challenging for people who are recognizably biracial or minorities. Do you know anyone who has experienced these challenges in Japan?