“Fashion is more art than art is.”

—Andy Warhol

1. Historical & Vintage Fashion

Historical fashions fascinate us and remind us of classic stories and tales. As the the decades pass, we remember some past trends with fondness and others with a shudder. Some people like to cosplay historical fashions at events like Renaissance fairs, and some even choose to wear historical fashions every day. Both of these groups find inspiration and support in online communities on social media, and some have created channels to teach the world about historical fashions. Here are a few examples:

Youtube Channels:

- Abby Cox

- Angela Clayton

- Bernadette Banner

- Crows Eye Productions

- Early American

- Elin Abrahamsson

- Karolina Zebrowska

- Lee-Am

- Morgan Donner

- Nicole Rudolph

- Pinsent Tailoring

- Prior Attire

- Rachel Maksy

- Sewstine

- Victoria Shelg

The following videos teach us specifically about fashion changes in the 20th century:

100 Years of Fashion:

~ Glamour: Evolution (of Fashion)

~ Allure: 100 Years of Beauty

~ Glam, Inc: 100 Years of Fashion

~ Real Women: Beauty Throughout the Decades

Documentation of historic Native American clothing is not as mainstream on social media, but there is a lot of information available in various places:

- North America: History of Indigenous Peoples’ Dress

- Clothing of Native American Cultures

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Dress in The Pre-Columbian Americas

- Illinois Stories: Native American Clothes and Beads (Joel, the first hobbyist, shares a lot of important cultural knowledge.)

- Fashion History: Native American

Unfortunately, most of it is not from Native sources, and some of it is reductionist. For the best information, please investigate exhibits in museums such as the National Museum of the American Indian or look for information from specific Native tribes and people.

2. Current Fashions

Fashion trends are notoriously fickle, and sometimes it’s hard to know what is in fashion. For centuries, many Anglophone and continental European women relied on “fashion plates” to see the latest styles. In the late 19th century, fashion magazines were created. Many of these magazines still exist, but some would say that they no longer set the trends; they merely track trends for their readers. Nowadays, fashion trends are spread on the internet across the globe. However, some fashion organizations have preserved their cultural status. Here is a list of iconic fashion magazines:

- Harper’s Bazaar (women’s fashion)

- InStyle (mostly women’s fashion)

- Glamour (women’s fashion)

- Vogue (mostly women’s fashion)

- Elle (women’s fashion)

- Stylist (women’s fashion)

- GQ (men’s fashion)

- Esquire (men’s fashion)

- Ebony (men’s and women’s fashion)

- Essence (all genders fashion)

- Kolor (men’s fashion)

- CRWN Mag (hairstyles)

Another place to find fashion trends is at celebrity events, such as movie premieres and the Met Gala, and fashion shows.

~ The Met Gala (2021 Livestream)

~ New York Fashion Week

~ London Fashion Week

~ Australian Fashion Week (2021 Analysis)

~ British Fashion Council Fund Show

~ Chanel Fashion Show

~ Indigenous Fashion Week: Toronto, Vancouver

~ A Red Berry Woman Native Fashion Show

~ Alter-NATIVE: Yellowtail Fashion Show (mini-series)

Very recently, Native designers have gotten more attention from the fashion industry. Here are some examples of their work:

- Native Fashion Now: Contemporary Native American Fashion

- 7 Native Fashion Designers You Need to Discover

- 7 Beautiful Native-Owned Fashion Brands to Know and Love

- 10 Indigenous Fashion Designers to Know

- 17 Indigenous Clothing Brands to Support and Follow

- How 6 Indigenous Designers Are Using Fashion to Reclaim Their Culture

- 15 Indigenous Designers on What Sustainable Fashion Is Missing

3. Cultural Appropriation

Note: In this article, “Native” refers to Native American peoples, including American Indians, Canadian Aboriginals, and other indigenous communities in the Americas.

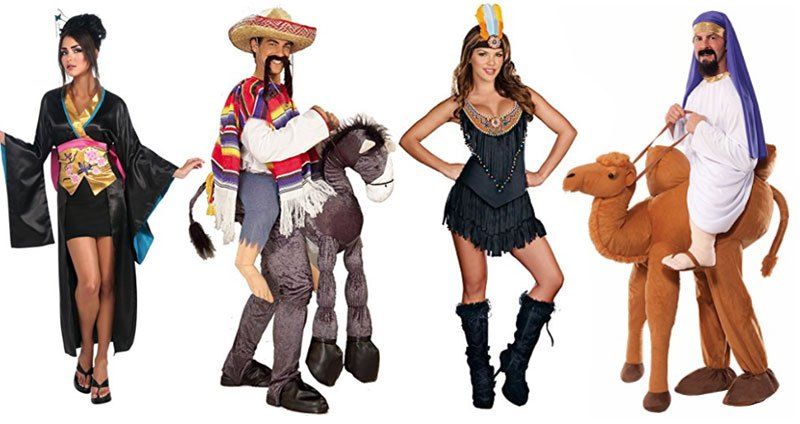

No discussion of modern fashion would be complete without addressing the concept of cultural appropriation. Cultural appropriation happens when a dominant culture uses important traditional styles and/or materials from another culture without (1) giving credit to the original designers, (2) maintaining the original intent of the design, or (3) showing proper respect for the traditions. One of the most famous examples is that, over the decades, many European Americans have worn feather headdresses and other “Native-inspired” costumes at Halloween or at music festivals. These costumes are using Plains Indians regalia without respecting their cultural importance. In severe cases, the appropriation uses a dehumanizing context, as seen in the “Pocahottie” costumes.

The Actual Worst: Who’s ruining it for everyone?

Cultural appropriation is usually an immediate cause for offense when a majority social group “adopts” a style or practice that they had previously attacked (or continue to attack) in people from a minority group. Examples of “adopted” practices include Native clothing and regalia, hairstyles originating in the Black community, or the bindi. Cultural appropriation can also be worsened through poor behavior that is exhibited specifically while publicly displaying the appropriated designs. (One of the most extreme examples of cultural appropriation is the rebranding of the swastika.) The use of Plains and Eastern Woodlands regalia as a “fashion statement” is offensive in itself because it exoticizes (風変わりにする) and entangles distinct cultures, and it does so in such a manner that it undermines one of their actual common points: a focus on sustainability. But the most dehumanizing aspect is certain people’s tendency to behave in exaggerated, aggressive manners while wearing the fake regalia, drawing from false stereotypes and caricatures of Native peoples.

The Main Argument: Who disagrees?

Cultural appropriation continues because not everyone agrees that it is bad, nor which forms of it are negative, nor who can engage in cultural appropriation. Some people see cultural appropriation as simply a form of “cultural exchange”, which is positive. Other times, attempts to call out appropriation of one tradition are seen as ignoring another tradition, as many cultures have traditions that meet the same basic definition but are distinct. Since cultural appropriation is hotly debated, calls for change are often mired in arguments. Many times, only the advice of “neutral” non-minority writers is respected, ignoring the original objections of the offended communities.

The Economics: Who benefits?

Cultural appropriation has also taken the form of economic exploitation, both in cheap “fast fashion” and in high fashion. Cheap “fast fashion” produces poorly designed, unsustainable costumes made by underpaid workers for consumerist markets while disrespecting other cultures’ traditions and the environment simultaneously. Meanwhile in high fashion, Native American designers are often underrepresented in major modern fashion shows (if present at all), but non-Native mainstream designers often use themes from Native cultures without permission and have great financial success with those designs. This appropriation is particularly offensive to Native people who still remember the days of Western boarding school uniforms and indigenous cultural repression.

In fact, financial exploitation is a major part of the cultural appropriation conversation. Even non-Native designers who actively work with Native communities may find themselves in exploitative roles. Here is a discussion of cultural appropriation by Native designers:

The Culture Policing: Who decides?

Similar to Native peoples, Black Westerners have faced extensive discrimination against their hair, clothing, and cultural identity over the past 500 years, and they are poorly represented in the fashion industry, sometimes only appearing as “exotic” or “a new fad” on the runway for other communities’ financial gain. For example, some designers have used fake cornrow wigs instead of hiring Black models with cornrows. In fact, while Native communities often face more issues with appropriation of their traditional clothing and regalia, the Black community is usually more strongly affected by appropriation of their hairstyles. (See: Black Hair Is ‘Ghetto’ Until Proved Fashionable).

Here are several discussions about hairstyles and the Black community:

- Protective Hairstyles in the Black Community

- The Reason Non-Black People Should Not Wear Black Hairstyles Is Actually Very Simple

- Watch This Documentary on Braids and Appropriation in America | ELLE

- Why And When Is It Offensive For Non-Black Women To Wear Black Hairstyles?

- Cornrows and Cultural Appropriation: The Truth About Racial Identity Theft

- OPINION: Black Culture Is Not Yours to Take

- Why the Conversation About Cultural Appropriation Needs to Go Further

There is also a new trend among social media influencers to engage in “blackfishing,” or pretending to be Black. This is just a new manifestation of Amandla Stenberg’s concerns in her video, Don’t Cash Crop on my Corn Rows. Negative reactions to the trend have been swift, but it continues to profit from views and media attention, even if that attention is negative.

The Final Say: Who gets it?

Overall, cultural appropriation is a complex and sensitive topic for many communities. A commonly voiced frustration among the both the Black and the Native communities, as well as other underrepresented groups, is that other people are redefining and explaining their problems on their behalf instead of listening to their communities. This discussion includes links to a variety of Black and Native perspectives, as well as a few Indian ones, but there are other voices across the globe and the conversation is constantly evolving. If you want to know more about a particular community’s opinions on the topic, please look for their voices online or visit the community and ask them!

“Fashion changes, but style endures.”

— coco chanel